|

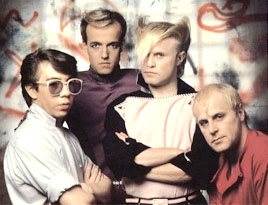

| It was the 1980s, a lot of crap was flying around. But I liked A Flock of Seagulls...just not the hair. |

I'm inclined to agree with the crap part. English is weird enough without all the superlatives. Thanks to the BBC History Magazine, we can blame the bored people in the 1400s. Many were first recorded in the 15th century in publications known as Books of Courtesy: manuals on the various aspects of noble living, designed to prevent young aristocrats from embarrassing themselves by saying the wrong thing at court.

The earliest of these documents to survive to the present day was The Egerton Manuscript, dating from around 1450, which featured a list of 106 collective nouns. Several other manuscripts followed, the most influential of which appeared in 1486 in The Book of St Albans – a treatise on hunting, hawking and heraldry, written mostly in verse and attributed to the nun Dame Juliana Barnes (sometimes written Berners), prioress of the Priory of St Mary of Sopwell, near the town of St Albans. This list features 164 collective nouns, beginning with those describing the ‘beasts of the chase’, but extending to include a wide range of animals and birds.

According to the Oxford dictionary, most are fanciful or humorous terms which probably never had any real currency, but have been taken up by antiquarian writers, notably Joseph Strutt in Sports and Pastimes of England (1801).

Some of my favorites:

a blush of boys

a bevy of ladies

a faith of merchants

a pity of prisoners

a clowder or glaring of cats

a herd of cranes

a busyness of ferrets

a fluther or smack or jellyfish

a watch of nightingales

an unkindness of ravens

a drift of wild pigs

a zeal of zebras

|

| A cute clowder of cats! Mew! |