The two main colors of Halloween are orange and black. Orange is a symbol of strength and endurance. It also is linked to the harvest and autumn. Black is a symbol of death and darkness, traditional themes of Halloween.These two colours play into the origins of halloween. The holiday was derived from the Celtic festival of Samhain, where the boundaries between life and death were blurred, with autumn being the natural blurring of summer ending and the winter beginning.

| The Rutabagas of the dammed! |

Black cats have a long history of being associated with the occult and death outside of Halloween. In ancient Egypt, cats were sacred and black cats possessed magic powers. During the festival of Samhain, worshipers believed that by using evil powers, humans could turn themselves into cats. According to legend, many cats were thrown into the fires to get of rid the evil. Black cats in medieval Europe were also believed to be witches' companions or familiars. Now we know better: cats are just cats and being black has no significance. It's unfortunate that some people still believe such nonsense so black cats are seen as un-adoptable by many. Here's a video to prove them wrong:

There are two other animals that are associated with Halloween in Europe: owls and bats.Owls were common symbols of wisdom and hidden knowledge, and that included the occult. Traditionally, large Halloween bonfires were built and would encourage a large amount of bugs to gather, causing owls and bats to swoop above the bonfires. Superstitions also suggest that owls ate the souls of the dying, their screeches and their glassy stare are an omen of death and disaster. The nocturnal nature of these animals played well into the festival of the night. Bats have become a more popular image in North America, partially due to their association with vampires and witches, which are said to turn into bats at will.

|

| I'm coming for your soul! |

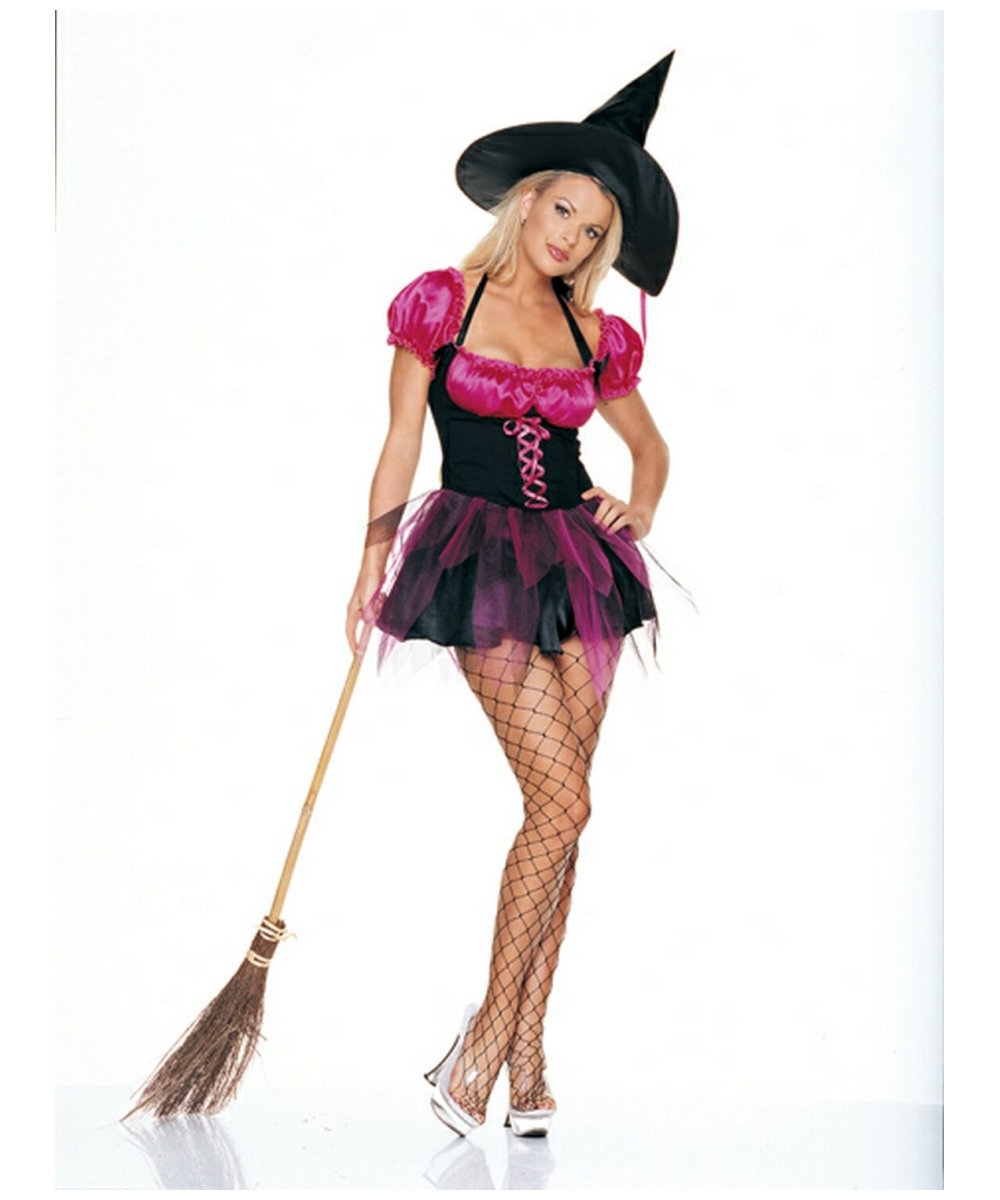

Finally, why are witches associated so strongly with Halloween? In the Celtic pre-christian world, it was believed Witches gathering twice a year when the seasons changed, on April 30 and the eve of October 31. Their magic was supposed to be very powerful on these two days. The fear of witches continued to be part of Christianity, as wise women were seen to be in league with the devil. Multiple witch hunts in the western world resulted in hundreds of men and women being murdered. The hunting down of witches then was misogynistic and anti-pagan, and by accusing people of being witches the historic Christians earn a special spot on my shit list. I'm not sure what the people of the past would think of our new interpretations: sexist yes, scary no.

|

| I don't think she has a license for those...brooms. |